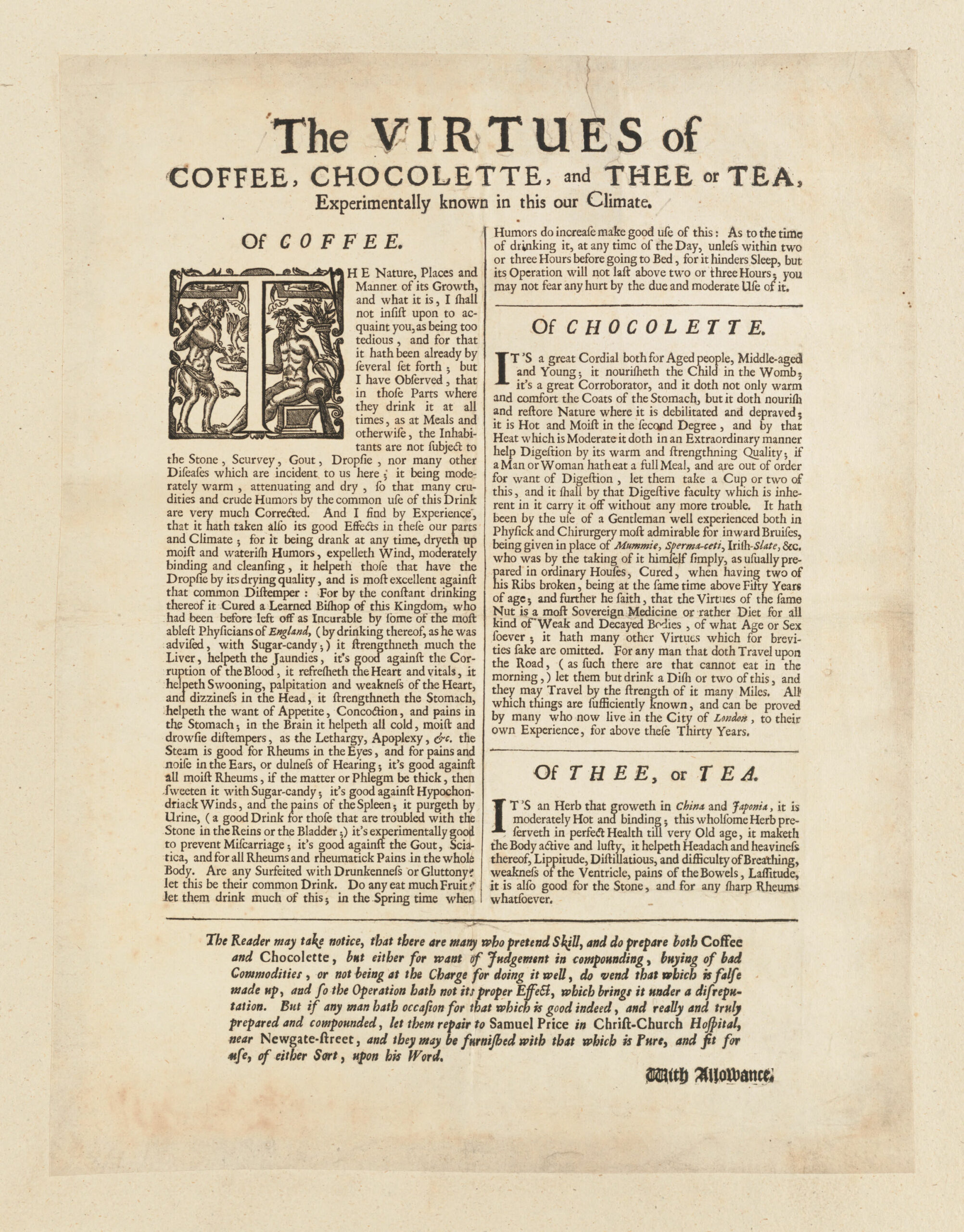

“The Virtues of Coffee” Explained in 1690 Ad: The Cure for Lethargy, Scurvy, Dropsy, Gout & More

According to many historians, the English Enlightenment may never have happened were it not for coffeehouses, the public sphere where poets, critics, philosophers, legal minds, and other intellectual gadflies regularly met to chatter about the pressing concerns of the day. And yet, writes scholar Bonnie Calhoun, “it was not for the taste of coffee that people flocked to these establishments.”

Indeed, one irate pamphleteer defined coffee, which was at this time without cream or sugar and usually watered down, as “puddle-water, and so ugly in colour and taste [sic].”

No syrupy, high-dollar Macchiatos or smooth, creamy lattes kept them coming back. Rather than the beverage, “it was the nature of the institution that caused its popularity to skyrocket during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.”

How, then, were proprietors to achieve economic growth? Like the owner of the first English coffee-shop did in 1652, London merchant Samuel Price deployed the time-honored tactics of the mountebank, using advertising to make all sorts of claims for coffee’s many “virtues” in order to convince consumers to drink the stuff at home. In the 1690 broadside above, writes Rebecca Onion at Slate, Price made a “litany of claims for coffee’s health benefits,” some of which “we’d recognize today and others that seem far-fetched.” In the latter category are assertions that “coffee-drinking populations didn’t get common diseases” like kidney stones or “Scurvey, Gout, Dropsie.” Coffee could also, Price claimed, improve hearing and “swooning” and was “experimentally good to prevent Miscarriage.”

Among these spurious medical benefits is listed a genuine effect of coffee—its relief of “lethargy.” Price’s other beverages—“Chocolette, and Thee or Tea”—receive much less emphasis since they didn’t require a hard sell. No one needs to be convinced of the benefits of coffee these days—indeed many of us can’t function without it. But as we sit in corporate chain cafes, glued to smartphones and laptop screens and mostly ignoring each other, our coffeehouses have become somewhat pale imitations of those vibrant Enlightenment-era establishments where, writes Calhoun, “men [though rarely women] were encouraged to engage in both verbal and written discourse with regard for wit over rank.”

Related Content:

“The Vertue of the COFFEE Drink”: An Ad for London’s First Cafe Printed Circa 1652

Philosophers Drinking Coffee: The Excessive Habits of Kant, Voltaire & Kierkegaard

How Humanity Got Hooked on Coffee: An Animated History

The Birth of Espresso: The Story Behind the Coffee Shots That Fuel Modern Life

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.“The Virtues of Coffee” Explained in 1690 Ad: The Cure for Lethargy, Scurvy, Dropsy, Gout & More

Read More...RIP David Sanborn: See Him Play Alongside Miles Davis, Randy Newman, Sun Ra, Leonard Cohen and Others on His TV Show Night Music

It’s late in the evening of Saturday, October 28th, 1989. You flip on the television and the saxophonist David Sanborn appears onscreen, instrument in hand, introducing the eclectic blues icon Taj Mahal, who in turn declares his intent to play a number with “rural humor” and “world proportions.” And so he does, which leads into performances by Todd Rundgren, Nanci Griffith, the Pat Metheny Group, and proto-turntablist Christian Marclay (best known today for his 24-hour montage The Clock). At the end of the show — after a vintage clip of Count Basie from 1956 — everyone gets back onstage for an all-together-now rendition of “Never Mind the Why and Wherefore” from H.M.S. Pinafore.

This was a more or less typical episode of Night Music, which aired on NBC from 1988 to 1990, and in that time offered “some of the strangest musical line-ups ever broadcast on network television.” So writes E. Little at In Sheep’s Clothing Hi-Fi, who names just a few of its performers: “Sonic Youth, Miles Davis, the Residents, Charlie Haden and His Liberation Orchestra, Kronos Quartet, Pharoah Sanders, Karen Mantler, Diamanda Galas, John Lurie, and Nana Vasconcelos.”

One especially memorable broadcast featured “a 15-minute interview-performance by Sun Ra’s Arkestra that finds the composer-pianist-Afrofuturist at the peak of his experimental powers, moving from piano to Yamaha DX‑7 and back again while the Arkestra flexes its cosmic muscles.”

“Sanborn hosted the eminently hip TV show,” writes jazz journalist Bill Milkowski in his remembrance of the late saxman, who died last weekend, “not only providing informative introductions but also sitting in with the bands.” One night might see him playing with Al Jarreau, Paul Simon, Marianne Faithfull, Bootsy Collins, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Dizzy Gillespie, — or indeed, some unlikely combination of such artists. “The idea of that show was that genres are secondary, an artificial division of music that really isn’t necessary; that musicians have more in common than people expect,” Sanborn told DownBeat in 2018. “We wanted to represent that by having a show where Leonard Cohen could sing a song, Sonny Rollins could play a song, and then they could do something together.”

Having wanted to pursue that idea further since the show’s cancellation — not the easiest task, given his ever-busy schedule of live performances and recording sessions across the musical spectrum — he created the YouTube channel Sanborn Sessions a few years ago, some of whose videos have been re-uploaded in recent weeks. But much also remains to be discovered in the archives of the original Night Music for broad-minded music lovers under the age of about 60 — or indeed, for those over that age who never tuned in back in the late eighties, a time period that’s lately come in for a cultural re-evaluation. Thanks to this YouTube playlist, you can watch more than 40 broadcasts of Night Music (which was at first titled Sunday Night) and listen like it’s 1989.

Related content:

How American Bandstand Changed American Culture: Revisit Scenes from the Iconic Music Show

All the Music Played on MTV’s 120 Minutes: A 2,500-Video Youtube Playlist

When Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party Brought Klaus Nomi, Blondie & Basquiat to Public Access TV (1978–82)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...A Playlist of the 3,300 Best Films & Documentaries on Youtube, Including Works by Hitchcock, Kubrick, Errol Morris & Other Auteurs

?si=yCx1pqpcATHND90L

Once upon a time, the most convenient means of discovering movies was cable television. This held especially true for those of us who happened to be adolescents on a break from school, ready and willing morning, midday, or night to sit through the commercial-laden likes of Corvette Summer, Transylvania 6–5000, BMX Bandits, or Freejack. Click on any of those links, and you can watch the relevant picture free on Youtube; click on the link to this playlist, and you’ll find 3,000 of the best films now available on that platform (the exact number may vary depending on your region of the world), as curated by Learnoutloud.com.

?si=rXFzge1fowoHfHxR

Not all these movies belong in the cheap-thrills bin. You’ll also find the work of celebrated auteurs like Alfred Hitchcock (The Man Who Knew Too Much, The 39 Steps), Stanley Kubrick (Fear and Desire, Barry Lyndon), Akira Kurosawa (Dersu Uzala, Dreams), and Woody Allen (Mighty Aphrodite, Cassandra’s Dream).

Then here are the documentaries, gathered here on their own playlist, including Errol Morris’ Gates of Heaven and The Thin Blue Line and Werner Herzog’s The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner and Lessons of Darkness. You can even find related pictures across genres: consider following Lost in La Mancha, which documents Terry Gilliam’s thwarted efforts to make The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, with The Man Who Killed Don Quixote.

?si=iEzCzwxZXCYcw8Up

“Almost all of these movies are free with ads,” writes Learnoutloud.com’s David Bischke, though YouTube Premium subscribers will be able to watch ad-free. “Like any streaming service, the rights to these movies change frequently, especially on YouTube’s official Movies and TV channel. So if you see a movie you really want to watch, then check it out soon!” If you’ve been meaning to get into Raise the Red Lantern and To Live by director Zhang Yimou, to learn about artists and musicians like Jackson Pollock and Glenn Gould, or to behold a young Arnold Schwarzenegger’s early appearances in Pumping Iron and Hercules in New York, now’s the time. And with Vice Versa and Dream a Little Dream currently available, why not revisit the subgenre of the eighties body-switch comedy while you’re at it?

P.S. In case you’re wondering about the legality of the films, the Learnoutloud site notes: To make the playlist, “the movies had to be legally free on YouTube either from YouTube’s official Movies and TV channel, from a YouTube channel legally distributing the movie, or from a movie on YouTube that is in the public domain.” Just thought you might want to know…

Related content:

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

Watch More Than 400 Classic Korean Films Free Online Thanks to the Korean Film Archive

Download 6600 Free Films from The Prelinger Archives and Use Them However You Like

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Meet Fanny, the First Female Rock Band to Top the Charts: “They Were Just Colossal and Wonderful, and Nobody’s Ever Mentioned Them”

When the Beatles upended popular music, thousands of wannabe beat groups were born all over the world, and many of them–for the first time ever, really–were all-female groups. This Amoeba Records article has a fairly exhaustive list of these girl bands, with names like The Daughters of Eve, The Freudian Slips, The Moppets, The Bombshells, and The What Four. Very few got past a few singles.

Instead, it would take until the 1970s for an all-female rock band to crack the charts. And no, it wasn’t the Runaways.

Formed in Sacramento by two Filipina sisters, Jean and June Millington, the group known as Fanny would be the first all-female band to release an album on a major label (their self-titled debut, on Reprise, 1970) and land four singles in the Billboard Hot 100–the title track from their 1971 album Charity Ball, a cover of Marvin Gaye’s “Ain’t That Peculiar” (as seen above), “I’ve Had It,” and finally “Butter Boy,” their highest chart success, at #29 in 1975. That last track was Jean Millington’s song about David Bowie, with whom she’d had a brief fling while touring the UK.

Born to a Filipina mother and a white American serviceman father, the two sisters found refuge in music when life at their Sacramento middle school was intimidating and racist. Rock music, however, was a way to make friends and find a support system. In their teens, they started a band called The Svelts, and watched as various other band members came and went due to marriage, or boyfriends who insisted they stop making music. The Millingtons didn’t stop, and having gained reliable band members in Addie Lee on guitar and Brie Brandt on drums, they followed their rhythm section to Los Angeles, changed the band name to Wild Honey, and wound up getting signed to Reprise after changing the name one more time to Fanny.

Though the man who signed them, Mo Ostin, considered them a novelty act, they were soon sent out on tour to open for groups like The Kinks and Humble Pie. They also backed Barbra Streisand on her Barbra Joan Streisand album, when the singer wanted a rockier sound.

In a 1999 Rolling Stone interview, David Bowie still sang their praises: “They were one of the finest fucking rock bands of their time, in about 1973. They were extraordinary: they wrote everything, they played like motherfuckers, they were just colossal and wonderful, and nobody’s ever mentioned them. They’re as important as anybody else who’s ever been, ever; it just wasn’t their time.”

After five albums and some personnel changes (including bringing in Patti Quatro, Suzi Quatro’s sister), the band called it quits. Jean would go on to marry Bowie’s guitarist Earl Slick; June came out as gay and later established the Institute for Musical Arts, which supported the women’s music movement.

Fanny dropped from rock consciousness, more or less, and are rarely brought up when pioneering women in rock are mentioned. June Millington still bristles about it, telling the Guardian, “All these women carved out their careers and I never once heard them mention Fanny…I looked. I waited. I read interviews. And I never saw it.”

They reunited in 2018 for an album, Fanny Walked the Earth, bringing back June, Jean, and Brie for a batch of politically charged songs and celebrity appearances by Runaways singer Cherie Currie, Kathy Valentine of the Go-Go’s and Susanna Hoffs and Vicki Peterson of the Bangles.

Rhino Records also rereleased their first four albums in a box set in 2002, for those who would like to investigate further.

Related Content:

New Web Project Immortalizes the Overlooked Women Who Helped Create Rock and Roll in the 1950s

Four Female Punk Bands That Changed Women’s Role in Rock

How Joan Jett Started the Runaways at 15 and Faced Down Every Barrier for Women in Rock and Roll

Chrissie Hynde’s 10 Pieces of Advice for “Chick Rockers” (1994)

Chrissie Hynde’s 10 Pieces of Advice for “Chick Rockers” (1994)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.

Read More...Read 20 Short Stories From Nobel Prize-Winning Writer Alice Munro (RIP) Free Online

Note: Back in 2013, when Alice Munro won the Nobel Prize in Literature, we published a post featuring 20 short stories written by Munro. Today, with the sad news that Alice Munro has passed away, at the age of 92, we’re bringing the original post (from October 10, 2013) back to the surface–in part because you can still read the 20 stories free online. Please find the stories at the bottom of this post.

Calling her a “master of the contemporary short story,” the Swedish Academy awarded 82-year-old Alice Munro the Nobel Prize in Literature today. It is well-deserved, and hard-earned (and comes not long after she announced her retirement from fiction). After 14 story collections, Munro has reached at least a couple generations of writers with her psychologically subtle stories about ordinary men and women in Huron County, Ontario, her birthplace and home. Only the 13th woman writer to win the Nobel, Munro has previously won the Man Booker Prize in 2009, the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction in Canada three times (1968, 1978, and 1986), and two O. Henry Awards (2006 and 2008). Her regional fiction draws as much from her Ontario surroundings as does the work of the very best so-called “regional” writers, and captivating interactions of character and landscape tend to drive her work more so than intricate plotting.

Of that region she loves, Munro has said: “It means something to me that no other country can—no matter how important historically that other country may be, how ‘beautiful,’ how lively and interesting. I am intoxicated by this particular landscape… I speak the language.” The language she may have learned from the “brick houses, the falling-down barns, the trailer parks, burdensome old churches, Wal-Mart and Canadian Tire.” But the short story form she learned from writers like Carson McCullers, Flannery O’Connor, and Eudora Welty. She names all three in a 2001 interview with The Atlantic, and also mentions Chekhov and “a lot of writers that I found in The New Yorker in the fifties who wrote about the same type of material I did—about emotions and places.”

Munro was no young literary phenom—she did not achieve fame in her twenties with stories in The New Yorker. A mother of three children, she “learned to write in the slivers of time she had.” She published her first collection, Dance of the Happy Shades in 1968 at 37, an advanced age for writers today, so many of whom have several novels under their belts by their early thirties. Munro always meant to write a novel, many in fact, but “there was no way I could get that kind of time,” she said:

Why do I like to write short stories? Well, I certainly didn’t intend to. I was going to write a novel. And still! I still come up with ideas for novels. And I even start novels. But something happens to them. They break up. I look at what I really want to do with the material, and it never turns out to be a novel. But when I was younger, it was simply a matter of expediency. I had small children, I didn’t have any help. Some of this was before the days of automatic washing machines, if you can actually believe it. There was no way I could get that kind of time. I couldn’t look ahead and say, this is going to take me a year, because I thought every moment something might happen that would take all time away from me. So I wrote in bits and pieces with a limited time expectation. Perhaps I got used to thinking of my material in terms of things that worked that way. And then when I got a little more time, I started writing these odder stories, which branch out a lot.

Whether Munro’s adherence to the short form has always been a matter of expediency, or whether it’s just what her stories need to be, hardly matters to readers who love her work. She discusses her “stumbling” on short fiction in the interview above from 1990 with Rex Murphy. For a detailed sketch of Munro’s early life, see her wonderful 2011 biographical essay “Dear Life” in The New Yorker. And for those less familiar with Munro’s exquisitely crafted narratives, we offer you below several selections of her work free online. Get to know this author who, The New York Times writes, “revolutionized the architecture of short stories.”

“Voices” - (2013, Telegraph)

“A Red Dress—1946” (2012–13, Narrative—requires free sign-up)

“Amundsen” (2012, The New Yorker)

“Train” (2012, Harper’s)

“To Reach Japan” (2012, Narrative—requires free sign-up)

“Axis” (2001, The New Yorker — in audio)

“Gravel” (2011, The New Yorker)

“Fiction” (2009, Daily Lit)

“Deep Holes” (2008, The New Yorker)

“Free Radicals” (2008, The New Yorker)

“Face” (2008, The New Yorker)

“Dimension” (2006, The New Yorker)

“Wenlock Edge” (2005, The New Yorker)

“The View from Castle Rock” (2005, The New Yorker)

“Passion” (2004, The New Yorker)

“Runaway” (2003, The New Yorker)

“Some Women” (2008, New Yorker)

“The Bear Came Over the Mountain” (1999, The New Yorker)

“Queenie” (1998, London Review of Books

“Boys and Girls” (1968)

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Wes Anderson Directs & Stars in an Ad Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of Montblanc’s Signature Pen

One hardly has to be an expert on the films of Wes Anderson to imagine that the man writes with a fountain pen. Maybe back in the early nineteen-nineties, when he was shooting the black-and-white short that would become Bottle Rocket on the streets of Austin, he had to settle for ordinary ballpoints. But now that he’s long since claimed his place in the top ranks of major American auteurs, he can indulge his taste for painstaking craftsmanship and recent-past antiquarianism both onscreen and off. For a brand like Montblanc, this surely made him the ideal choice to direct a commercial celebrating the hundredth anniversary of their flagship writing tool, the Meisterstück.

Shot at Studio Babelsberg in Germany, where Anderson is at work on his next feature The Phoenician Scheme, the resulting short “features Anderson himself, sporting a wispy walrus mustache, as well as frequent collaborators Jason Schwartzman and Rupert Friend, all posing as a group of mountain-climbers with a particular affection for the freedom and inspiration offered by Montblanc’s products,” writes Indiewire’s Harrison Richlin.

Within its first minute, “the ad takes us from the cold, snowy caps of Mont Blanc to a cozy chalet Anderson announces as The Mont Blanc Observatory and Writer’s Room.” Vogue Business’ Christina Binkley reports that this indoor-to-outdoor transition alone required 50 takes, which was only one of the surprises in store for Montblanc’s marketing officer.

Anderson also turned up with an unexpected proposal of his own. “The filmmaker presented a prototype pen of his own design that he asked the German company to manufacture,” Binkley writes. “He’d even named it: the Schreiberling, which means ‘the scribbler’ in German. That had not been part of the pitch.” Perhaps convinced by the built prototype assembled by Anderson’s set-design team, Montblanc “agreed to produce 1,969 copies of this small, green fountain pen to commemorate Anderson’s birth year, 1969.” At 55 years of age, Anderson may no longer be the preternaturally confident young filmmaker we remember from the days of Rushmore or The Royal Tenenbaums, but since then, he’s only grown more adept at getting exactly what he wants from a company, whether it be a movie studio or a European luxury-goods manufacturer.

Related Content:

Wes Anderson’s Shorts Films & Commercials: A Playlist of 8 Short Andersonian Works

Montblanc Unveils a New Line of Miles Davis Pens … and (Kind of) Blue Ink

Why Do Wes Anderson Movies Look Like That?

Has Wes Anderson Sold Out? Can He Sell Out? Critics Take Up the Debate

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Hannah Arendt Explains How Totalitarian Regimes Arise–and How We Can Prevent Them

“Adolf Eichmann went to the gallows with great dignity,” wrote the political philosopher Hannah Arendt, describing the scene leading up to the prominent Holocaust-organizer’s execution. After drinking half a bottle of wine, turning down the offer of religious assistance, and even refusing the black hood offered him at the gallows, he gave a brief, strangely high-spirited speech before the hanging. “It was as though in those last minutes he was summing up the lesson that this long course in human wickedness had taught us — the lesson of the fearsome word-and-thought-defying banality of evil.”

These lines come from Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, originally published in 1963 as a five-part series in the New Yorker. Eichmann “was popularly described as an evil mastermind who orchestrated atrocities from a cushy German office, and many were eager to see the so-called ‘desk murderer’ tried for his crimes,” explains the narrator of the animated TED-Ed lesson above, written by University College Dublin political theory professor Joseph Lacey. “But the squeamish man who took the stand seemed more like a dull bureaucrat than a sadistic killer,” and this “disparity between Eichmann’s nature and his actions” inspired Arendt’s famous summation.

A German Jew who fled her homeland in 1933, as Hitler rose to power, Arendt “dedicated herself to understanding how the Nazi regime came to power.” Against the common notion that “the Third Reich was a historical oddity, a perfect storm of uniquely evil leaders, supported by German citizens, looking for revenge after their defeat in World War I,” she argued that “the true conditions behind this unprecedented rise of totalitarianism weren’t specific to Germany.” Rather, in modernity, “individuals mainly appear in the social world to produce and consume goods and services,” which fosters ideologies “in which individuals were seen only for their economic value, rather than their moral and political capacities.”

In such isolating conditions, she thought, “participating in the regime becomes the only way to recover a sense of identity and community. While condemning Eichmann’s “monstrous actions, Arendt saw no evidence that Eichmann himself was uniquely evil. She saw him as a distinctly ordinary man who considered obedience the highest form of civic duty — and for Arendt, it was exactly this ordinariness that was most terrifying.” According to her theory, there was nothing particularly German about all of this: any sufficiently modernized culture could produce an Eichmann, a citizen who defines himself by participation in his society regardless of that society’s larger aims. This led her to the conclusion that “thinking is our greatest weapon against the threats of modernity,” some of which have become only more threatening over the past six decades.

Related content:

Take Hannah Arendt’s Final Exam for Her 1961 Course “On Revolution”

Watch Hannah Arendt’s Final Interview (1973)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...George Orwell’s Political Views, Explained in His Own Words

Among modern-day liberals and conservatives alike, George Orwell enjoys practically sainted status. And indeed, throughout his body of work, including but certainly not limited to his oft-assigned novels Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, one can find numerous implicitly or explicitly expressed political views that please either side of that divide — or, by definition, views that anger each side. The readers who approve of Orwell’s open advocacy for socialism, for example, are probably not the same ones who approve of his indictment of language policing. To understand what he actually believed, we can’t trust current interpreters who employ his words for their own ends; we must return to the words themselves.

Hence the structure of the video above from Youtuber Ryan Chapman, which offers “an overview of George Orwell’s political views, guided by his reflections on his own career.” Chapman begins with Orwell’s essay “Why I Write,” in which the latter declares that “in a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer.”

His awakening occurred in 1936, when he went to cover the Spanish Civil War as a journalist but ended up joining the fight against Franco, a cause that aligned neatly with his existing pro-working class and anti-authoritarian emotional tendencies.

After a bullet in the throat took Orwell out of the war, his attention shifted to the grand-scale hypocrisies he’d detected in the Soviet Union. It became “of the utmost importance to me that people in western Europe should see the Soviet regime for what it really was,” he writes in the preface to the Ukrainian edition of the allegorical satire Animal Farm. “His concerns with the Soviet Union were part of a broader concern on the nature of truth and the way truth is manipulated in politics,” Chapman explains. An important part of his larger project as a writer was to shed light on the widespread “tendency to distort reality according to their political convictions,” especially among the intellectual classes.

“This kind of thing is frightening to me,” Orwell writes in “Looking Back on the Spanish War,” “because it often gives me the feeling that the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world”: a condition for the rise of ideology “not only forbids you to express — even to think — certain thoughts, but it dictates what you shall think, it creates an ideology for you, it tries to govern your emotional life as well as setting up a code of conduct.” Such is the reality he envisions in Nineteen Eighty-Four, a reaction to the totalitarianism he saw manifesting in the USSR, Germany, and Italy. “But he also thought it was spreading in more subtle forms back home, in England, through socially enforced, unofficial political orthodoxy.” No matter how supposedly enlightened the society we live in, there are things we’re formally or informally not allowed to acknowledge; Orwell reminds us to think about why.

Related content:

An Animated Introduction to George Orwell

George Orwell Reveals the Role & Responsibility of the Writer “In an Age of State Control”

George Orwell Explains in a Revealing 1944 Letter Why He’d Write 1984

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...A New Analysis of Beethoven’s DNA Reveals That Lead Poisoning Could Have Caused His Deafness

Despite the intense scrutiny paid to the life and work of Ludwig van Beethoven for a couple of centuries now, the revered composer still has certain mysteries about him. Some of them he surely never intended to clarify, like the identity of “Immortal Beloved”; others he explicitly requested be made public, like the cause of his death. The trouble is that, for generation after generation, nobody could quite figure out what that cause was. But recent genetic analysis of his hair, which we first featured last year here on Open Culture, has shed new light on the matter of what killed Beethoven — or rather, what increasingly ailed him up until he died at the age of 56.

This effort “began a few years ago, when researchers realized that DNA analysis had advanced enough to justify an examination of hair said to have been clipped from Beethoven’s head by anguished fans as he lay dying,” writes the New York Times’ Gina Kolata.

With the genuine samples separated from the frauds, a test for heavy metals revealed that “one of Beethoven’s locks had 258 micrograms of lead per gram of hair and the other had 380 micrograms”: 64 times and 95 times the normal amount, respectively. Chronic lead poisoning, possibly caused by Beethoven’s habit of drinking cheap wine sweetened with “lead sugar,” could have caused the “unrelenting abdominal cramps, flatulence and diarrhea” that plagued him in his lifetime.

It could also have hastened the deafness that had become nearly complete by age thirty. “Over the years, Beethoven consulted many doctors, trying treatment after treatment for his ailments and his deafness, but found no relief,” Kolata writes. “At one point, he was using ointments and taking 75 medicines, many of which most likely contained lead.” Alas, the true danger of lead poisoning, a condition that had been acknowledged since antiquity, wouldn’t be taken seriously until the late nineteenth century. According to the research so far, even this degree of lead exposure wouldn’t have been fatal by itself. But with a bit less of it, would Beethoven have completed his tenth symphony, or even continued on to an eleventh? Add that to the still-growing list of unanswerable questions about him.

Related content:

The Secrets of Beethoven’s Fifth, the World’s Most Famous Symphony

The Math Behind Beethoven’s Music

Read Beethoven’s Lengthy Love Letter to His Mysterious “Immortal Beloved” (1812)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Jerry Seinfeld Delivers Commencement Address at Duke University: You Will Need Humor to Get Through the Human Experience

This weekend, Jerry Seinfeld gave the commencement speech at Duke University and offered the graduates his three keys to life: 1. bust your ass, 2. pay attention, and 3. fall in love. Then, 10 minutes later, he added essentially a fourth key to life: “Do not lose your sense of humor. You can have no idea at this point in your life how much you’re going to need it to get through. Not enough of life makes sense for you to be able to survive it without humor.” “It is worth the sacrifice of an occasional discomfort to have some laughs. Don’t lose that.” “Humor is the most powerful, most survival-essential quality you will ever have or need to navigate through the human experience.” Amen.

Related Content

John Waters’ RISD Graduation Speech: Real Wealth Is Life Without A*Holes

Conan O’Brien Kills It at Dartmouth Graduation

Jon Stewart’s William & Mary Commencement Address: The Entire World is an Elective

Read More...